Mysterious Madagascar, famous for lemurs, baobabs, coral reefs, and exquisite vanilla, is a tropical island in the Indian Ocean. Bigger than Britain, France, or Canada, the island nation lies 300 miles off the coast of Africa and is considered a continent because of its massive size and abundant plant and animal biodiversity.

A ring-tailed lemur, found in Nosy Be, Madagascar — credit Canva

The southern African country, once covered by lush rainforests and fringed by four thousand square kilometres of pristine coral reefs, is rapidly losing these precious eco-systems due to forest degradation, soil run-off into the ocean, and coral bleaching caused by pollution and climate change.

One of the solutions to Madagascar’s environmental crisis is embracing sustainable tourism to support islanders’ livelihoods, boost the economy, restore coral reefs, and protect wildlife. We are looking for volunteer Reef Rangers to become reef protectors and actively engage in the many wildlife conservation projects run by the Madagascar Research and Conservation Institute, Turtle Cove, on the island of Nosy Komba.

Conservation Management and Sustainable Tourism

Local Child Drumming in a Madagascar Village — credit: Lily on Canva Pro

Madagascar is one of the best tropical island destinations for sustainable tourism because of the efforts of dedicated organisations like the Madagascar Research and Conservation Institute (MRCI), with which Reef Support has proudly partnered.

MRCI affiliates with the EU-sponsored Indian Ocean Commission to responsibly manage the marine environment and restore coral reefs by running a coral reef conservation program and a hawksbill and green sea turtle conservation project. Their other sustainability initiatives include a nudibranch research centre, forest restoration programs, regular beach clean-ups, and building vital infrastructure like clinics and schools — much needed in such a remote and impoverished destination.

Furthermore, the organisation works closely with Daughters of the Deep, a vibrant Australian Foundation that strives to empower young women of local communities by offering them scuba-diving certifications and secondary education. (Don’t miss the stunning video of their life-changing success stories here!).

How Local Community Empowerment Protects Natural Ecosystems

A Local Malagasy Woman walks across the beach with a hand-woven basket on her head — credit: Lily on Canva Pro

Recent research demonstrates that empowering local communities is the most effective way to protect and conserve the natural environment. Locals can learn to become self-sufficient and free themselves from poverty by harnessing natural resources to feed, clothe, and house themselves while protecting biodiversity. In this way, communities can generate much-needed economic revenue by supporting sustainable tourism — as long as they have access to the implements: knowledge, equipment, and education.

The Reef Ranger Volunteer Program with MRCI at Turtle Cove, Nosy Komba

Reef Support is seeking Reef Ranger volunteers to monitor, regrow, and restore coral reefs in the Lokabe Marine Protected Area and National Park, on the northwest coast of Madagascar.

Reef Rangers will learn advanced scuba diving techniques, how to protect marine life, and how to survey, monitor, and construct artificial reefs. Furthermore, they can participate actively in aiding communities to take sustainable action through education and by building schools and clinics for the disadvantaged. Volunteers enjoy their stay at the palm-fringed MRCI Turtle Cove camp on the tiny coral islet of Nosy Komba, a short boat trip from Nosy Be Island.

The Most Biodiverse Place on Earth

Madagascar is a mountainous island surrounded by corals in the Southwest Indian Ocean — credit: Lily on Canva Pro.

Madagascar, the eighth continent, was once part of the great ancient singular landmass of Gondwanaland millions of years ago. As the earth’s tectonic plates inch apart, this massive chunk of land slowly sliced off from the Indian sub-continent to the East — and separated from Africa to the West 150 million years later to become a rainforest island with beautiful marine life. Consequently, the island offers the planet’s most abundant plant and animal biodiversity — hosting a massive five percent of all species.

Ninety percent of all animals and trees of Madagascar are endemic to the island. However, their numbers are rapidly dwindling due to human impact, including widespread slash-and-burn agriculture, the farming of Zebu, a culturally-prized breed of drought-resistant cattle, and the booming ethnic population — now at 30 million.

The Unique Plants and Animals of Madagascar

A Black Lemur and baby, one of the three lemur species found on Nosy Komba, the Island of Lemurs — Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Madagascar became a biodiversity hotspot because the original wildlife arrived by sea on life rafts (funnily enough, just like in the comic movie of the same name) after the African and Asian continents split. The small evolutionary pool of early mammals, reptiles, birds, and primates experienced an ‘adaptive radiation’ or, in simple terms, an evolutionary explosion that filled all the diverse habitat niches available with a wondrous array of completely different animals to those found on the sister continents.

Covered by lush rainforests, crowned by a central volcanic and mountainous plateau, and fringed by stunning coral reefs, the magnificent island offered an incredible variety of environmental niches to fill. Ancient primates, existing before monkeys even evolved, grew into over 110 lemur species and adapted to occupy every possible jungle biome. r.The only animal that made it to Madagascar from Africa was the hippopotamus — in the form of the Malagasy pygmy hippo, now sadly believed to be extinct.

Another unusual evolutionary process called ‘convergent radiation’ occurred in Madagascar — where animals took on the characteristics of their mainland counterparts — to adapt to and fill the range of ecosystems and habitats on the Indian Ocean island. An example is the curious cat-like carnivorous tree-climbing fossa that descended from an ancient African mongoose to become the island’s main predator, filling the niche big cats occupy on other continents.

The Madagascan Fossa: A tree-climbing species of ancient African Mongoose that evolved to become the top predator of Madagascar — Credit: Lily on Canva Pro

Today, on the island of Madagascar, there are over 150 endemic species of rainbow-coloured chameleons, brilliant frogs, tortoises, bright lizards, gorgeous butterflies, unusual insects, iridescent birds, and cute aquatic mammals called tenrecs to see.

The Baobab Trees of Madagascar

The majestic trees of Madagascar: There are 6 species of Baobab on the Island — Credit: Canva Pro

Towering giant baobab trees, vibrant forest flowers, ferns, and jungle fruits provide homes and sustenance for this vast array of biodiverse wildlife. Many of these animals and plants face extinction due to poaching, habitat loss, pollution, and the adverse impacts of climate change.

A rainbow-coloured chameleon in the Madagascar Jungle: There are over 150 species — credit: credit: Canva Pro

The Tribal People of Madagascar

The first human settlers arrived in Madagascar by boat about 2000 years ago from Africa and Asia. The original people of the island were gentle folks who tilled the soil, fished the coral reefs, and hunted for food. They rarely engaged in warfare, and infrequent tribal clashes or border disputes led to minimal loss of life.

To this day, Madagascar is still a nation depending on the immediate environment for sustenance and daily survival, a third-world country struggling with the consequences of slash-and-burn agriculture, overfishing, deforestation, and ill-planned or non-existent infrastructure. Roads remain mostly unpaved, wifi is only available in cities and tourist resorts, and electricity is intermittent across the island. Citizens are reliant on old coal-burning power stations and diesel-run generators for their energy needs, systems that contribute to further pollution and the devastating effects of climate change.

The Madagascar Zebu: A breed of culturally prized drought-resistant cattle are farmed in Madagascar. Zebu are collector’s items for locals, although they produce little milk, and are seldom slaughtered. Their growing numbers are responsible for habitat damage on the island.

However, Madagascar has a colourful, vibrant, and diverse ethnic culture of friendly locals with a reputation for warmth and hospitality. There are over 18 tribes on the island, contributing to an astoundingly eclectic cultural flavour that primarily reflects ancestry from Southeast Asia and part-Arabic and African.

The spoken languages of Madagascar are French and Malagasy, a dialect still spoken in the interior of Borneo, reflecting the distant origins of the island’s people. The delicious cuisine consists of an abundance of organically cultivated and jungle fruits, locally grown rice, beans, freshly caught seafood, and delicacies like grilled deep ocean marlin or freshwater tilapia baked into the traditional curry, tomato, watercress and garlic dish called Trondro Gasy.

Coral Reef Marine Life of Madagascar

A Whale Shark Swimming in Madagascar’s blue waters — Credit Wikimedia Commons

There are over 300 endemic species of coral in the waters of Madagascar; the harder staghorn elkhorns, brain corals, and colourful soft corals. The reefs sustain 400 species of fish, including the endangered blue-spotted shark, endemic to the island. Madagascar’s turquoise waters also host over 30 species of cetaceans — 9 baleen and 21 toothed-whale species, including playful bottlenose, humpback, and spinner dolphins.

Whale Sharks visit the islands of Nosy Be and Nosy Komba around the end of every year, lingering through the rainy season. Manta rays, eagle rays, green, hawksbill, and loggerhead turtles, and scintillating reef fish circle the clear blue waters, while tiny crustaceans, nudibranchs, soft corals, and seahorses drift in the swaying seagrass beds, other protected eco-habitat associated with the coral reefs.

Third Biggest Barrier Reef

Madagascar reef — credit Lilly Canva

Madagascar has the highest diversity of coral reef structures in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), exceeding those of the Seychelles and Mauritius. The continent boasts the third-largest barrier reef at Tulear in the southwest — severely damaged by coral bleaching since 2016.

The Tulear Barrier Reef is a highly regulated Marine Protected Area (MPA) because maintaining coral reef biodiversity is vital for local survival. The reef supports the livelihoods of over 20 000 fishermen — and provides the primary protein nutrition for tens of thousands of people living in the arid and inhospitable south of the country.

However, coral banks and fringing reefs encompass a massive 3,934 km2 square kilometres along the coastline and encircle the 250 islands around Madagascar. Most of the continent’s coral reefs are along the protected western shorelines of the island.

Lokobe National Park, Nosy Be, is another one of 56 designated MPAs around the island continent, where the Marine Research and Conservation Institute monitors coral and sea conditions and restores coral reefs with permission from the Madagascar government.

MPAs Conserve Coral Reef Biodiversity

Madagascar’s beautiful marine life underwater — credit Lilly Canva Pro

Climate change, sedimentation from deforestation, overfishing, and pollution have caused a rapid loss of coral reef biodiversity around the island of Madagascar. Warming sea temperatures and increasingly acid ocean conditions aggravate corals, which spontaneously bleach — or lose their associated colourful symbiotic algae — in response to these changing values. Bleached corals may recover and regrow, if protected — and that is where MPAs play a vital role.

The Madagascar government has created over 50 MPAs around the island to protect the reefs from overfishing and unsustainable tourism. They are restricted — and only those with a permit may enter to conduct scientific research, regrow and regenerate corals, assist in fish stock recovery, and monitor and survey marine life. In some MPAs, sustainable fishing, and seafood aquaculture is permitted to feed and sustain local communities.

Building Artificial Reefs with MRCI in the Lokabe MPA

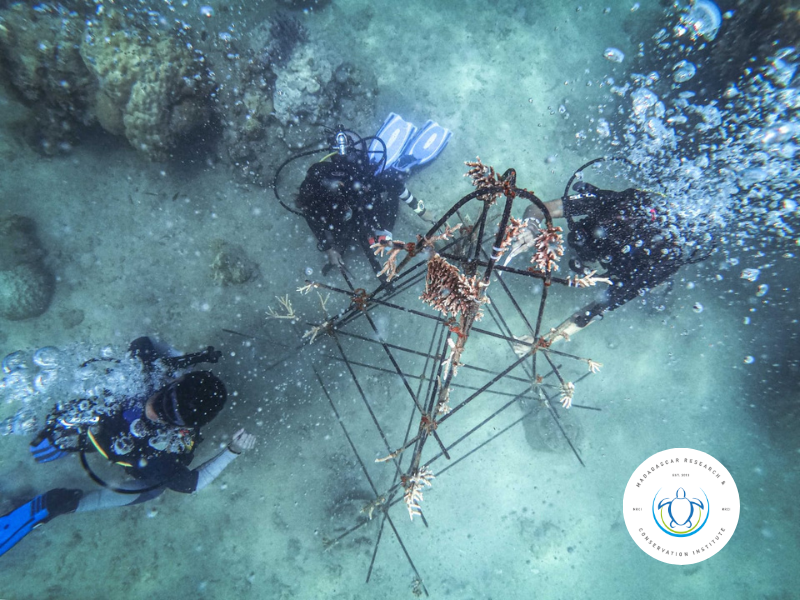

MCRI volunteers planting coral at Nosy Komba Madagascar — credit Madagascar Conservation and Research Institute

MRCI is constructing artificial reefs under the expert guidance of their Marine Biologist and Conservation and Outreach officer, Solomon Davids, and Marine Conservation Manager, Llewellyn Tossel. Both expert scuba conservation divers, train volunteers how to regrow damaged corals on metal frames set up underwater in front of the Turtle Cove Camp near the Lokabe MPA.

Opportunistic Fragmentation Techniques for Coral Restoration

MCRI volunteers engaged in opportunistic coral restoration at Nosy Komba Madagascar — credit Madagascar Conservation and Research Institute

David and Llewellyn employ a method of coral restoration called opportunistic coral fragmentation; only naturally broken coral fragments damaged by tidal forces, wind, or storms are regrown in the sea, rather than in a laboratory or temperature and pH-controlled indoor aquarium. Their method encourages coral resilience and bypasses the need for a constant power supply to pump water and maintain ambient conditions. It turns out that naturally fragmented corals will regrow at faster paces in the open ocean, in a similar way to their performance in a controlled lab where micro fragmentation was first discovered.

Exploring the Island of Lemurs | Best Scuba Diving in Madagascar

One of the most beautiful coves at Nosy Komba, Madagascar — credit: Lily Canva Pro

Reef Rangers will stay at Turtle Cove, the MRCI HQ on Nosy Komba, also known as Nosy Ambariovato. Known as the Island of Lemurs, Nosy Komba is only a few miles by boat from the Nosy Be, an island at the northwest tip of Madagascar with an international airport.

Tranquil Nosy Komba is covered with lush jungle, leaping with lemurs, and crowned with an ancient volcanic peak at its centre. The tiny isle, surrounded by clear turquoise waters and delicate coral reefs, is a beautifully preserved habitat — and the perfect location to learn more about caring for the environment. It’s a paradise where foreigners and locals alike can discover practical techniques to strengthen the links between humans and nature and ensure a sustainable, prosperous, and thriving future.

Best Times to Visit Madagascar

Whale Shark Season: Late September-December

Whale sharks visit the island in the rainy seasons from late December/ early January to March to feed on plankton blooms that well up periodically from the ocean’s depths. Recently, large groups of juvenile males were spotted congregating in the tranquil waters of Nosy Be. It is perfectly safe to scuba dive with these harmless and magnificent giants, breathtaking and unforgettable underwater. experience

Humpback Whale Season: July-November

Humpback whales travel an ancient migratory corridor from the Antarctic to breed and calve in the warm southern waters of the island in May and remain there throughout the dry season until December. It is inadvisable to approach a whale, especially a mother with a calf — and tourists watch whales from boats that remain at a respectful distance from the pod or the pair.

Turtle Egg Laying Season: October-April

Madagascar is home to five species of turtles: green sea turtles, olive ridley, and loggerhead turtles — hunted for their meat and eggs. The great hawksbill turtle, coveted for its shiny shell, is another, and the elusive leatherback sea turtle is seldom spotted. In the hottest months of the tropical year, sea turtles crawl slowly onto beaches at night to lay their eggs in the sand. MRCI volunteers and reef rangers monitor the turtle’s progress and protect the eggs from poachers and predators alike

Baby turtles are born after two months in the nest — buried deep in the sand. Turtle monitors will mark the sites of the nests — or move eggs to safety — and assist baby turtles in making the long and dangerous voyage back to the ocean.

A green turtle swimming over a seagrass meadow — Credit Wikimedia Commons

A Summary of the MRCI Projects for Reef Rangers in Madagascar

- PADI Advanced Scuba Diving Certification

- PADI Divemaster Scuba Diving Certification

- Artificial Reef Building and Coral Restoration

- Sea Turtle Conservation

- Nudibranch Research and Monitoring Program

- Community Empowerment Programs: Teaching, Education, and Building Infrastructure

Visit the Reef Support Destinations Page and sign up to become a Reef Ranger and citizen scientist on the stunning tropical Island of Lemurs in Madagascar. Learn to regrow and restore coral reefs and how to conserve and protect marine life through survey and monitoring techniques. Bring joy and happiness to locals by sharing your knowledge and environmental awareness with rural communities through sustainable tourism initiatives. The MRCI and Reef Support Teams look forward to having you on board!